This program was the world’s first post-disaster repair program to use a geographic-coordinate system, personal digital assistants (PDAs) and electronic real-time databases to assess an area, manage a large-scale project and ensure quality control. Based on the data collected in the repair assessment, the program pinpointed repair zones and trained local mason, engineers and construction managers to respond efficiently and accurately.

Miyamoto and its partners worked closely with Haiti’s Ministry of Public Works (known by its French Acronym of MTPTC) and proposed to them the possibility of conducting a detailed assessment of the buildings that had been impacted by the earthquake. MTPTC embraced the idea. Miyamoto brought in the United Nations Operations (UNOPS) with funding from the World Bank, and PADF obtained funding from the United States Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA—part of the United States Agency for International Development—USAID).

Miyamoto developed a slightly modified version of the ATC-20 form, the standard form used in California to rapidly assess earthquake damage, for use in Haiti. We then began training Haitian engineers to conduct the evaluation. The trained engineers were equipped with a PDA and sent in groups to completely canvas a neighborhood. At each structure, the engineer would use the PDA to take a picture of the building and the GPS coordinates. They then inspected the building, going through every room, and completed a short questionnaire on the building directly on the PDA. At the end of the inspection, each building was spray-painted with a highly visible tag that indicated whether the building was safe for use (“green-tagged”), damaged, but stable (“yellow-tagged”) or unstable (“red tagged”). Each engineer was able to inspect an average of 10 structures a day. At the end of each day, the data was downloaded directly into the central database. The teams were so large in time, that the program was able to inspect 1,700 structures a day.

Miyamoto developed a slightly modified version of the ATC-20 form, the standard form used in California to rapidly assess earthquake damage, for use in Haiti. We then began training Haitian engineers to conduct the evaluation. The trained engineers were equipped with a PDA and sent in groups to completely canvas a neighborhood. At each structure, the engineer would use the PDA to take a picture of the building and the GPS coordinates. They then inspected the building, going through every room, and completed a short questionnaire on the building directly on the PDA. At the end of the inspection, each building was spray-painted with a highly visible tag that indicated whether the building was safe for use (“green-tagged”), damaged, but stable (“yellow-tagged”) or unstable (“red tagged”). Each engineer was able to inspect an average of 10 structures a day. At the end of each day, the data was downloaded directly into the central database. The teams were so large in time, that the program was able to inspect 1,700 structures a day.

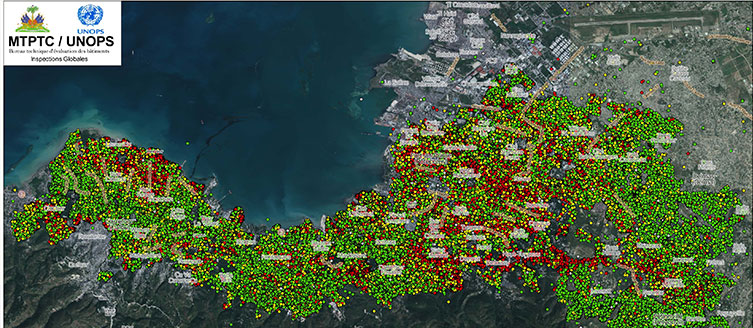

Through this program, more than 400,000 structures were tagged – amounting to nearly every building in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area that was impacted by the earthquake. The assessment showed that 53 percent of the houses were safe for use (green-tagged), 26 percent needed minor repairs to be made useable (yellow), and only 24 percent were unstable and needed either major repairs or to be demolished and rebuilt (red).

Initially, owners were reluctant to allow the engineers into their homes and were suspicious of the program. PADF and Miyamoto worked closely with its partners in the poor urban areas to convince the people to trust in the program. As the program grew and became better known, owners began seeking out the engineers and asking for advice.

One of the striking points that the assessment brought to light was how widespread the damage was. Rather than having a core area of red-tagged houses surrounded by rings of yellow-tagged and then green-tagged houses, nearly every neighborhood is a mixture of green, yellow and red tagged buildings. Furthermore, through an analysis of the levels of damage suffered by the different types of buildings, we found that residential buildings, schools and churches were the hardest hit and commercial buildings fared best.

Taken together, these facts reinforced the conclusion that poor quality of construction in Haiti and elsewhere is usually the main cause of the widespread building failures.

The most striking impact of the assessment on a human level was its role helping people return to green-tagged homes. The inspectors reported that before the assessment, roughly half of the houses that became green-tagged had been occupied. After the house was green-tagged, occupancy jumped to 80 percent, with most unoccupied houses being in neighborhoods that had predominantly yellow and red-tagged houses.